Faithful Conversations #132

Introduction to Readers

“History must be imagined before it can be understood.” (David Blight)

Philemon (fih-LEE-muhn), Paul’s shortest letter, shows up once every three years in the Revised Common Lectionary. Just 25 verses long, this oft-overlooked epistle opens a deeply personal window into the early Christian movement—a moment of moral tension, complex relationships, and spiritual transformation. After spending some time with Philemon, Paul, and Onesimus over the past several days, I decided to take the opportunity to explore the story more fully and will do that in my reflections. It is a fascinating letter.

Before getting to that, however, some further background is in order (and a good example of the difficulties inherent in Biblical interpretation). One of my guiding quotes regarding the study of history comes from Yale historian David Blight, reminding us that we must imagine a world far different from our own to bring history alive. Imagine this, for example. In the generation leading up to the Civil War, pro-slavery advocates and abolitionists BOTH drew on Biblical texts to support their contrary positions. Paul’s appeal to Philemon to receive Onesimus, his escaped slave, “no longer as a slave, but as a beloved brother” suggests that slavery was wrong, yet Paul’s letter was also used as an example of the Bible sanctioning human bondage. Soldier and author John Richter Jones, for example, argued just that in his 1861 treatise, Slavery Sanctioned by the Bible. Consider that as you explore it this week.

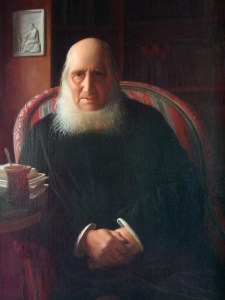

As always, thanks for your ongoing interest in the Lectionary! We have one commemoration on the ELCA calendar this week. Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig (b. 1783) was a Danish pastor, poet, historian, and educational reformer whose legacy reshaped both church and society. He championed a living Christianity rooted in sacramental tradition and cultural heritage, opposing sterile rationalism in favor of spiritual vitality. Grundtvig is best remembered for founding the folk high school movement, which democratized education and inspired a new Danish nationalism grounded in enlightenment, community, and human dignity. He died on 2 September in 1872. (Note: All commemorations within the ELCA calendar are found on pages 14-17 of our hymnal — the ELW).

** Note 1: Links to outside references are bolded and italicized and are meant for further reading or research on your part. While the text I am including in the blog is my own, I am pulling from a multitude of sites for ideas and connections.

** Note 2: In my increasing use of A.I. (Copilot), I will cite sourcing of how I am using the tool, if necessary. I don’t want that to be overly cumbersome, but I am gradually incorporating more tools. I am exploring the A.I. world this summer prior to my next teaching semester. As you can imagine, it is a great challenge right now and will forever change the face of education!

** Note 3: The images I include in the blog are drawn from Wikimedia Commons to the fullest extent possible.

Common Themes Among the Readings

Pentecost 13 Readings

Deuteronomy 30: 15-20

Psalm 1

Philemon 1-21

Luke 14: 25-33

My source for the Bible readings each week is the Bible Gateway website. I generally use the NRSVUE translation.

The readings for Pentecost 13 (Year C) center on the profound theme of choice and commitment in the life of faith. Deuteronomy 30 and Psalm 1 both present a stark contrast between the way of life and the way of death, urging the faithful to choose obedience and delight in God’s law as the path to flourishing. Luke 14 intensifies this call by demanding radical discipleship—renouncing possessions, relationships, and even self-interest to follow Christ wholeheartedly. In Philemon, Paul models this costly love by appealing for reconciliation and transformation, asking Philemon to receive Onesimus not as a slave but as a beloved brother. Together, these texts challenge believers to count the cost, embrace the cross, and walk the path of righteousness with courage and grace.

“Describe the common themes among the readings for Pentecost 13.” Copilot, 30 August 2025, Copilot website.

LUTHER’S METHOD OF BIBLE READING

A Revision of the Lectio Divina (Augustinian)

Three Steps

Oratio (Prayer): This is the starting point, where one humbly prays for the Holy Spirit’s guidance to understand God’s Word. Luther emphasized that prayer prepares the heart and mind to receive divine wisdom.

Meditatio (Meditation): This involves deeply engaging with Scripture, not just reading it but reflecting on it repeatedly. Luther encouraged believers to “chew on” the Word, allowing its meaning to sink in and shape their thoughts and actions.

Tentatio (Struggle): Often translated as “trial” or “temptation,” this refers to the challenges and spiritual battles that arise as one seeks to live according to God’s Word. Luther saw these struggles as a way God refines faith, making it more resilient and authentic.

The Second Reading: Philemon 1-21

Salutation

1 Paul, a prisoner of Christ Jesus, and Timothy our brother, To our beloved coworker Philemon, 2 to our sister Apphia, to our fellow soldier Archippus, and to the church in your house: 3 Grace to you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ.

Philemon’s Love and Faith

4 I thank my God always when I mention you in my prayers, 5 because I hear of your love for all the saints and your faith toward the Lord Jesus. 6 I pray that the partnership of your faith may become effective as you comprehend all the good that we share in Christ.7 I have indeed received much joy and encouragement from your love, because the hearts of the saints have been refreshed through you, my brother.

Paul’s Plea for Onesimus

8 For this reason, though I am more than bold enough in Christ to command you to do the right thing, 9 yet I would rather appeal to you on the basis of love—and I, Paul, do this as an old man and now also as a prisoner of Christ Jesus. 10 I am appealing to you for my child, Onesimus, whose father I have become during my imprisonment. 11 Formerly he was useless to you, but now he is indeed useful to you and to me. 12 I am sending him, that is, my own heart, back to you. 13 I wanted to keep him with me so that he might minister to me in your place during my imprisonment for the gospel, 14 but I preferred to do nothing without your consent in order that your good deed might be voluntary and not something forced. 15 Perhaps this is the reason he was separated from you for a while, so that you might have him back for the long term, 16 no longer as a slave but more than a slave, a beloved brother—especially to me but how much more to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord. 17 So if you consider me your partner, welcome him as you would welcome me. 18 If he has wronged you in any way or owes you anything, charge that to me. 19 I, Paul, am writing this with my own hand: I will repay it. I say nothing about your owing me even your own self. 20 Yes, brother, let me have this benefit from you in the Lord! Refresh my heart in Christ.21 Confident of your obedience, I am writing to you, knowing that you will do even more than I ask. 22 One thing more: prepare a guest room for me, for I am hoping through your prayers to be restored to you.

Final Greetings and Benediction

23 Epaphras, my fellow prisoner in Christ Jesus, sends greetings to you,24 and so do Mark, Aristarchus, Demas, and Luke, my coworkers. 25 The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ be with your spirit.

Take time to watch this excellent overview of Philemon from the Bible Project. We will be referencing the work of the Bible Project in our Bible 365 Challenge starting in late September, especially the summary videos. They are especially good if you are a visual learner!

Explore the Bible Project’s Website

Reflection: The Story of Onesimus

Paul is traditionally credited with thirteen letters in the New Testament. Of these, seven are considered undisputed—Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians, and Philemon—widely accepted as authentically Pauline. The remaining six—Ephesians, Colossians, 2 Thessalonians, 1 and 2 Timothy, and Titus—are disputed, raising questions about authorship, theological development, and historical context. Philemon stands apart in its intimacy. It centers on a triangular relationship: Paul, the imprisoned apostle; Philemon, a house church leader and slaveholder; and Onesimus, an enslaved man who has encountered Paul and returned transformed.

Here’s a review of the basic facts: Written from a prison cell around 60-62 CE, Paul’s letter to Philemon is his shortest — merely 355 Greek words long. The key figures are Philemon, a Christian leader and slave owner in Colossae, and Onesimus, his runaway slave who encountered Paul and became a believer (sidebar: we never hear from Onesimus). Paul sends Onesimus back to Philemon with this letter, appealing for reconciliation and a transformed relationship. Rather than commanding Philemon, Paul diplomatically urges him to receive Onesimus not as a slave, but as a beloved brother in Christ.

What can we take away from this personal correspondence from the earliest days of the Christian movement? First, the radical nature of the letter is best understood in context. In the Greco-Roman world of Paul’s time, slavery was a widespread and socially accepted institution, with enslaved people making up a significant portion of the population and serving in roles from manual labor to skilled professions. Estimates are that roughly 35% of the population was enslaved! Slaves were considered property with no legal rights, though manumission (freedom) was possible and sometimes led to citizenship. Enslavement wasn’t based on race but on status, and people became slaves through war, birth, or debt. Paul’s letter to Philemon boldly challenges this system by urging Philemon to see his slave Onesimus not as property but as a brother in Christ. Paul chooses his words carefully (note verse 8 and beyond) but leaves little doubt of his intentions.

Second, this somewhat obscure letter from 2000 years ago speaks to us across the ages. Imagine Paul and Onesimus sitting in that jail cell, working through the particulars of the letter. Imagine the fear that Onesimus must have experienced as he traveled back to his former master! His willingness, I suspect, sheds light on his relationship of trust with Paul. As spiritual descendants of this story, the Apostle’s call for radical reconciliation, dignity, and spiritual kinship that transcends social status is breath-taking. Paul’s appeal to Philemon invites believers to embody grace—not just in personal forgiveness, but in how they view and treat others, especially those marginalized or wronged. Our challenge is to move beyond transactional relationships and embrace a community defined by love, mutual respect, and shared identity in Christ. How will we respond to that challenge?

Soli Deo Gloria!

Postscript: What happened to Onesimus? There is much mystery there. Onesimus became a symbol of Christian transformation and reconciliation. After encountering Paul in Rome and converting to Christianity, he returned to Philemon bearing Paul’s appeal for mercy and brotherhood. Early church tradition holds that Onesimus was later freed and rose to prominence as a church leader, possibly serving as bishop of Ephesus. His legacy endures as a testament to grace, justice, and the radical reordering of relationships within the early Christian community.

Prayer Reflection: The Imitation of Christ

(1380-1472)

The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis is a 15th-century devotional classic that urges readers to renounce worldly vanities and cultivate a life of humility, self-denial, and spiritual intimacy with Christ. Structured in four books, it offers meditative reflections on the interior life, the comfort of divine presence, and the transformative power of the Eucharist. Revered across centuries and traditions, it remains one of the most widely read Christian texts after the Bible, guiding seekers toward a quiet, contemplative discipleship. Here is a representative passage:

The life of a good religious person should shine in all virtue and be inwardly as it appears outwardly . . . We ought every day to renew our purpose in God, and to stir our hearts to fervor and devotion, as though it were the first day of our conversion. And we ought daily to pray and say: Help me, my Lord Jesus, that I may persevere in good purpose and in your holy service unto my death, and that I may now today perfectly begin, for I have done nothing in time past.

A Musical Offering: The Doxology (some nostalgia here)

The well-known doxology that begins “Praise God from whom all blessings flow” was written by Anglican Bishop Thomas Ken in the late 1600s as part of hymns for students at Winchester College. First published in 1709, it quickly became a regular part of Christian worship, loved for its brief and powerful praise of the Trinity. Its style echoes older Jewish and early Christian traditions, where short songs of praise were used in prayer and worship. The tune often used for the doxology is called the “Old Hundredth,” written by Louis Bourgeois in 1551 for the Genevan Psalter, a Reformation-era songbook. (Note: The familiar hymn, “All People That on Earth Do Dwell,” is the tune associated with the Doxology — it is hymn 883 in the ELW). Though originally paired with Psalm 134, it became famous through Psalm 100 (“Old Hundredth”) and remains a central melody in Protestant worship because of its strong, simple beauty and deep historical roots. Like many of you, I grew up with this song, and especially associate it with potluck suppers in church basements or family gatherings at Thanksgiving and Christmas — and yes, how well I recall my father always having to clarify, ahead of time, how we were going to finish the song! (there are two versions of the last line) And, there were always those in our midst that manage to include rich harmonies during the “Amen!” The musical interpretation I posted here comes from jazz pianist Chuck Marohnic. Feel free to sing along!

Various Lyrics Associated With the Doxology

(The original)

Praise God from whom all blessings flow,

Praise Him all creatures here below,

Praise Him above, ye heavenly host,

Praise Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.

And Prayers Before Eating (especially in church basements!)

Be present at our table, Lord;

Be here and everywhere adored.

Thy children bless, and grant that we

May feast in paradise with Thee. Amen.

Or . . .

Be present at our table, Lord;

Be here and everywhere adored.

Thy mercies bless, and grant that we

May strengthened for Thy service be. Amen.

Chuck Marohnic (b. 1940) is a renowned jazz pianist and educator whose career has spanned collaborations with legends like Chet Baker and Joe Henderson, as well as decades of teaching at Arizona State University. After retiring from academia, he turned his focus toward integrating jazz with spiritual practice, serving as a music minister in various Christian denominations. He co-founded Sanctuary Jazz, blending sacred themes with improvisational depth.

Faithful Conversations Updates

Regular worship will resume this week at ELC at 9:30. Sunday is also designated across the ELCA as “God’s Work, Our Hands” Sunday and after an abbreviated service, we will have a variety of activities going on related to that. Our in-person lectionary discussions will resume on Sunday, 14 September.

📖 Ready to read the Bible in a year?

Starting in late September, join our Bible 365 Challenge—a yearlong journey through Scripture for individuals, families, and groups. As Lutherans, we know God’s Word shapes our lives and deepens our faith. Luther once said, “The Bible is alive… it lays hold of me.” Whether you choose the print path or go digital, we’ll grow together—with daily readings, mutual support, and spiritual connection. Details are coming soon. Let’s dive in, walk together, and let the Word come alive in us!